Chawkundi Art, one of the two oldest galleries in Karachi, recently presented “Sabza o Gul,” an exhibition featuring the works of seven artists, based on a quote from Ghalib - “From whence come the foliage and the flower? What is cloud? What is air?” The collection created a refreshing atmosphere of serenity and tranquility, and as there were comparatively few works presented, the artists’ individuality was not buried under an avalanche of colour and form. In its diversity the show celebrated the fertile artistic imagination as the garden of the soul.

While ruminating on these works, it was hard to forget the Garden of Eden in all its perfection, even the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, a marvel of ancient engineering and the only one of the 7 Wonders of the World whose location has never been definitely established. On the one hand it is said to be the creation of Nebuchadnezzar II near present-day Hillah in Iraq, for his Median wife Queen Amytis, who longed for the greenery of her native country; on the other hand it may have been built in Nineveh by King Sennacherib. Meanwhile, in ancient Greece there flourished many kinds of gardens – sacred groves, private and religious parks.

In the ancient Middle East, happiness was associated with enclosures rather than with open spaces, owing to the harsh world of nature outside, so the garden was a kind of peaceful oasis. Wild nature is generally subdued and controlled in the garden, and in modern psychology such places are often taken as symbols of the conscious mind, as opposed to the forest, which stands for the dark, tangled, rooted growth of the unconscious; while in literature, art and dreams, gardens and landscapes frequently stand for ideas, beliefs, moods, things not fully expressible in language.

Dr. Ali Akbar of IVS in his address at Chawkandi titled ‘Fragrance and the Heart in Grecoarab (Yunani) Medicine’, remarked that, “aroma and aromatic substances evoked pleasant and sensual responses in Indo-Islamic culture...fragrances played an important part in the creation of “atmospheres” for habitation.”

Along with ideas of perfume and flora, the breath, with its physiological and mystical significance, played its part in the exhibition. This appeared in Madiha Sikander’s gouache on wasli “Gulshan wala Ghur”, featuring an architect’s plan of her own former habitation in Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi; this context turning the painting into a symbol of loss. Charming in its execution and symmetry, it shows portraits of 12 children arranged like a floral necklace surrounding the house, somehow like the creatures once believed to inhabit the air, and representing the 12 months of the years in which they lived, laughed and cried, or went to play. They in turn are surrounded by a wondrously executed cloud formation, whose receding form and darkening colour demonstrate how the present merges with the past. The children breathe upon the house, as if to remind it of their former presence, and to blow life back into it.

[quote]In the ancient Middle East, happiness was associated with enclosures rather than with open spaces[/quote]

Pondering on the present status of the place, I recalled my own sense of loss on seeing the wood of my childhood home neatly stacked up for use as firewood by the new owners of the property when I revisited it some 30 years later. Meanwhile, Madiha’s house plan suggests other plans made during the lifetime of this place and its erstwhile inhabitants. How many came to fruition, or were abandoned like the house presented here?

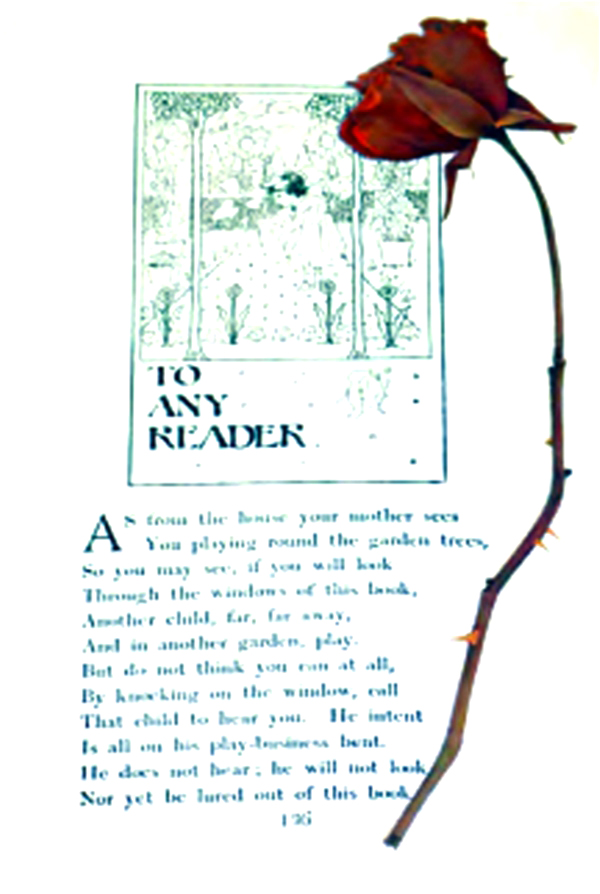

Her second exhibit, titled “All that Can’t be Left Behind,” is of her own treasured copy of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “A Child’s Book of Poetry,” opened at a page where the poet quietly laments the way that children leave the garden, grow up and move away. “And it is but a child of air / That lingers in the garden there”. The artist has painted an exquisite and eloquent faded rose on the page, as if to bring back something of those days.

[quote]The dareecha as an opening can be an entry either to a different set of circumstances, or to a higher plane[/quote]

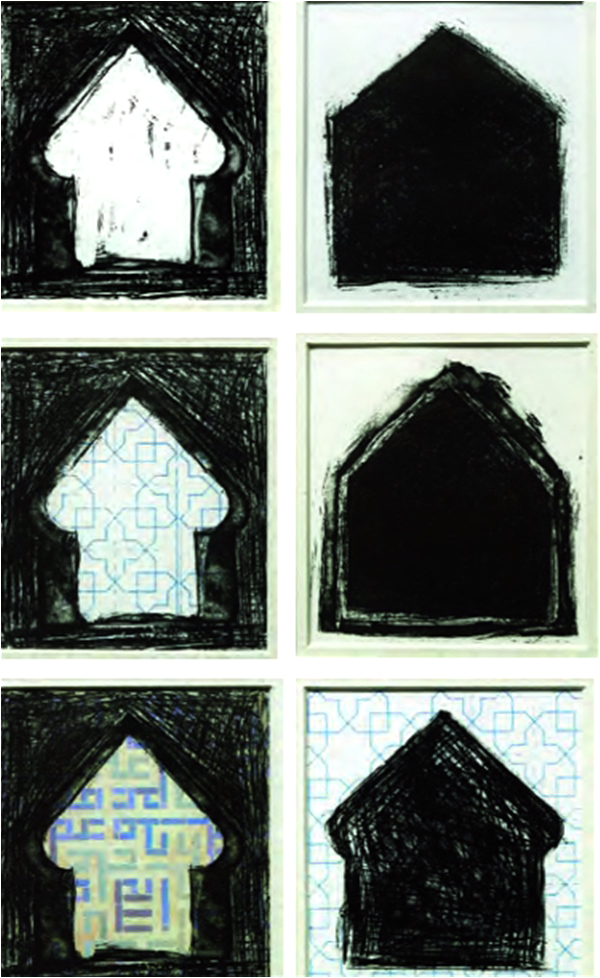

“The door opened, in came the breeze. I wondered whether the wound was healed or not. The breeze said ‘No.’” Meher Afroz quotes these lines of poetry as the thought provoking basis of her mysterious “Khula Dareecha,” a set of 6 etchings. The dareecha as an opening can be taken as a symbol of hope, an entry either to a different set of circumstances, or to a higher plane, or at least as an escape from torment. If we trace this image anti-clockwise, we note the gradual opening of the dareecha in the slowly lightening blackness. Then the casement gradually opens further, as our eye travels upwards, revealing first a maze of lines, then a jaali in floral geometric style. Finally there is the open casement, with its suggestion of life beyond, in the faint suggestions of form. But that is all. So the wound, whatever its nature and cause, has not healed. And we must step forth into the open, back into life, to find the cure.

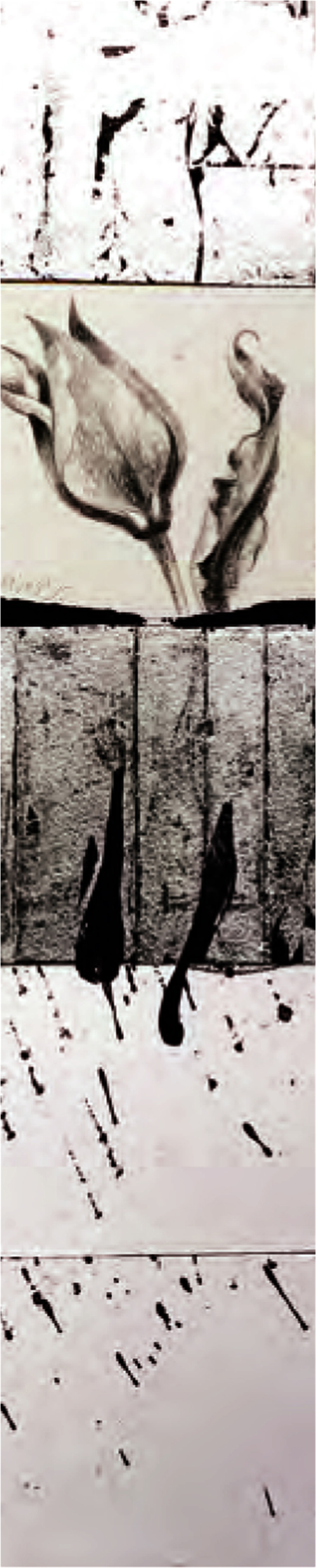

This piece was the most visually spectacular part of the exhibition. Meher’s fascinating installation, skillfully combining five wonderful etchings and a series of flower paintings in acrylic, graphite and silver leaf, included a wide range of techniques, media and textures. Interestingly, it has been suggested that the direct mark of the graphite and the point at which pieces of paper are joined are significant pathways of tests, quests and hardships that mirror the journey of life, in preparation for the ultimate journey.

Such profundity is typical of Meher’s work. But what of the flowers themselves? Roses dominate the scene, in varying stages from bud to fully blown or falling, and each of these images with its portion of silver leaf, shaped as a grid in the manner of the miniature aesthetic, features moonlit water, now in a pond edged by blue and silver triangles, now beautiful in its freedom. And the suggestion of strife from the outside world is seen here and there in the black and silver gratings, the raindrops and the water ruffled by a contrary wind. In one picture sandals appear with a falling rose, indicating the start of a more difficult stage of the path, while now and then the lotus, the Buddhist symbol of purity, arises. So these things embody the aforementioned tests, quests and hardships.

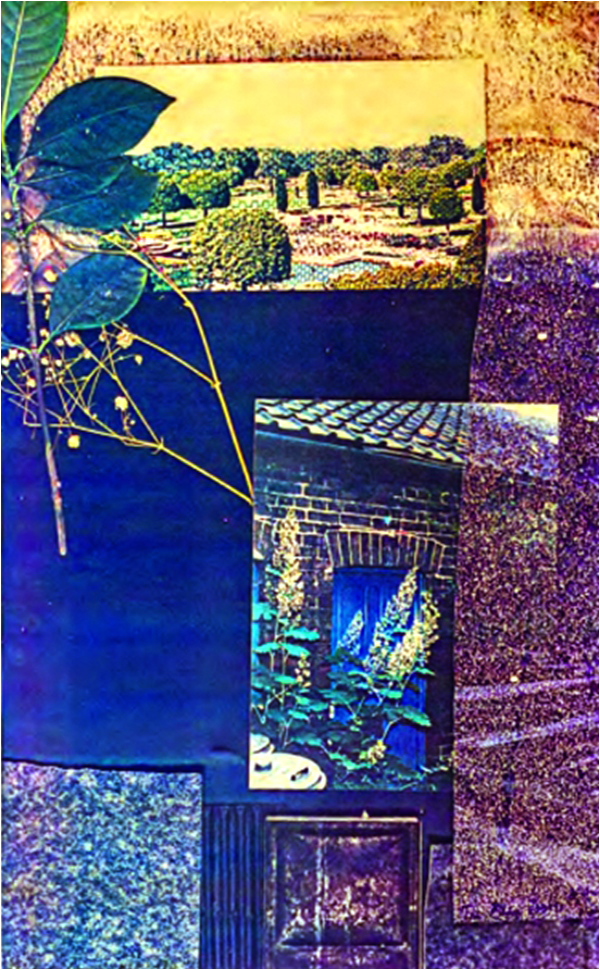

Naz Ikramullah’s etching, “The Blue Door”, is the work of an artist who has regarded several foreign places including London as home, and therefore this piece appears like a page from an old European album. The door in its setting is a literal image, faithfully detailed and evoking nostalgia for the old-style English house with its plentiful flower gardens. However, her image is verdant oasis in the surrounding desert, a place with a far-reaching vista, perhaps reaching into eternity as our reward for enduring the vicissitudes of life. And tranquility is there in her muted colour scheme. There is indeed much to see, but without the distraction of too much colour.

We ponder upon how to enter the blue door, recollecting children’s stories like “The Secret Garden,” and the many fairytales with forbidden doors. But the piece with its far-reaching vista suggests boundless freedom within the enclosure - echoing Plato’s dictum that freedom is found in obedience to certain laws. However, the sturdy plants in front of the door give rise to a question. How long is it since anyone opened this portal, and what has prevented this?

The trees in this piece, and those in Ghalib Baqar’s fascinating watercolour “Naqsh-e-Junoon”, open a wide field of philosophical speculation, since with its roots drawing strength from the earth, and its head reaching for the sky, it is frequently seen as an image of the world and all nature - as the Tree of Life. The network of branches springing from the trunk suggests a complex pattern unifying all things. And the idea of the immortality of trees, particularly the evergreen species, goes far back into history, while representations of sacred trees are to be found in the remnants of early civilisations, the Tree of Life is one of the sacred trees in the garden of Eden.

While Baqar’s “Nakhl-e-Gumaan” evokes the perfume of the flower garden, his “Naqsh-e-Junoon”, besides its relevance to the above, shows the tree, despite its strength, as subject to the forces of nature like wind. The surrounding border has been peeled back, revealing the artist’s inner garden, and the rustic barriers in front, with the river behind it, suggest barriers to be crossed before reaching the garden itself - in this instance a place of delightful, rich colour.

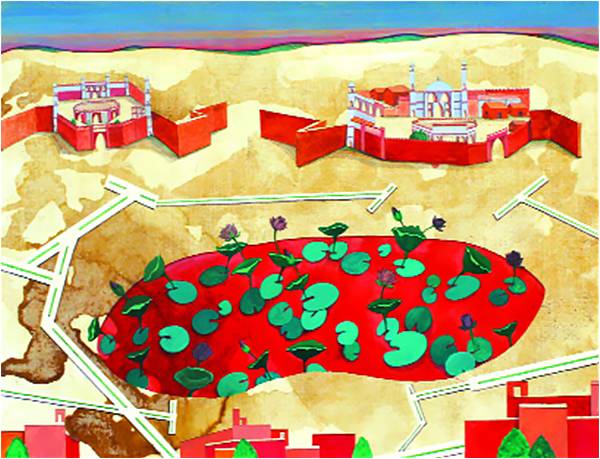

“Yume no Machi” is an oil on canvas exhibit by Farooq Mustafa, who divides his time between Pakistan and Mito City in Japan, and whose art studies included a course at the University of Tsukuba in Japan - hence the Japanese title, meaning “Town of my Dreams.” Actually its title is borrowed from an extremely popular Japanese cartoon, introduced in 2003 by a Japanese artist resident in New York, and still going strong. The word “machi’ is loosely applied to settlements including towns, cities and suburbs or smaller areas of inhabitation. (See Kenkyusha’s Japanese-English Dictionary.)

There is an air of fragility about his mosques and houses, surrounded by a continuous wall, thus reminiscent of the inner city of Lahore; and this part of the picture contains elements of the Mughal miniature in contrast with the box-like lines of the modern structures below, structures all to frequently seen in Japan. The central pool of red water, home to many lotus flowers, along with the skillfully variegated wash, blends well with the rest of the composition, while on the horizon appear the green countryside backed by the sea. However, the somewhat maze-like paths form the most intriguing element, since the maze sometimes appears in gardens as an arrangement of hedges or paths – easy to enter but difficult to escape from. To penetrate a maze and return from it symbolized spiritual death and resurrection in ancient Greece. Meanwhile, the texture of the canvas and the knotted wood of the frame add to the charm of Farooq’s piece.

However, Zarina Hashmi’s black and white woodcut, “Rani’s Garden,” with its considerable impact seemed like the anchor of “Sabza o Gul.” The piece is a tribute to her sister Rani, a person greatly loved by many, and in the slight discolouration of the paper plus the wearing off of the gold patina in the outer four corners is an indication of the age of the composition. There is a rustic charm, too, in its execution, with its simplicity and bold lines. It is an image of purity and simplicity, redolent of the love between sisters.

“Sabza o Gul” was the first in a series of exhibitions based on the garden emerging from the artist’s imagination. Its reference to Ghalib’s famous verse in his “Diwan-e-Glalib” happens magically and effortlessly, confirming that the artistic imagination remains unbound by the scientific or the logical.