We are all witnesses to this scenario: a distant relative is spirited away and kept in seclusion, after which those who knew them look at each other in sage understanding and nod whenever their name is mentioned.

Even the Queen of England has not escaped. One episode in Season 4 of The Crown reveals the Queen Mother’s secret Bowes-Lyon cousins who were kept in a sanatorium for most of their lives, away from the public gaze. It is only when Princess Margaret sought professional help that the therapist disclosed the need to explore the family history. The cousins she had presumed dead are actually in a sanatorium to avoid the social stigma of the time.

Though The Crown takes creative liberties with the story, the Queen Mother’s reaction is all too familiar: “Their illness, idiocy and imbecility will make people question the integrity of the bloodlines. Can you imagine the headlines if that were to get out?”. This conversation could easily play out among many blue-bloods in any country.

Mental health issues are almost never spoken of publicly, particularly when marriages are being arranged. And in some cases, marriage is even considered a 'solution' to mental health issues. The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed that more than ever mental health issues can no longer be ignored. They need to be confronted directly, openly and compassionately.

Burying one’s secrets in the sand or deliberately ignoring such issues does not evaporate them. This is not the stuff of books. One has only to look about one to see that mental health issues abound. They need to be dealt with through patience, care, kindness and more often than not: professional help.

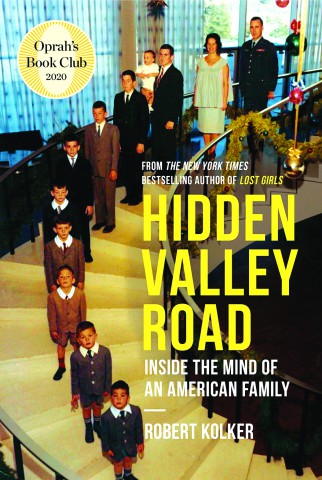

If you have not done so, please do read Read Hidden Valley Road by Robert Kolker, chosen by Oprah Winfrey for her book club pick in 2020. It is an actual account of a family of twelve children, born to Catholic parents in America during the 1950s. It is a riveting story - too wild yet true - of how mental illness can destroy families. The book is gripping: weaving a narrative using the genres of reporting and narrative non-fiction interleaved with the science of trauma and disease.

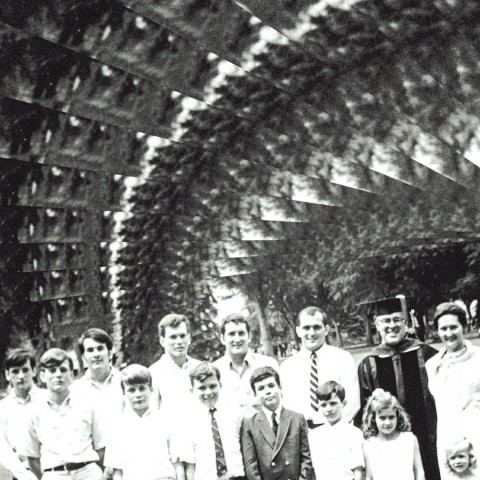

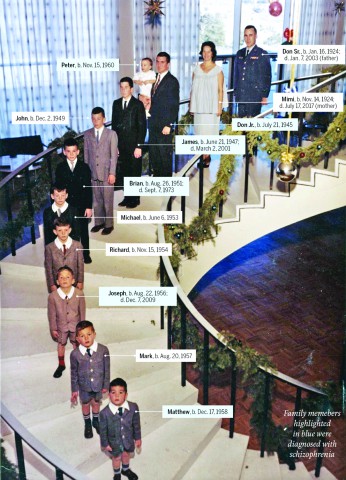

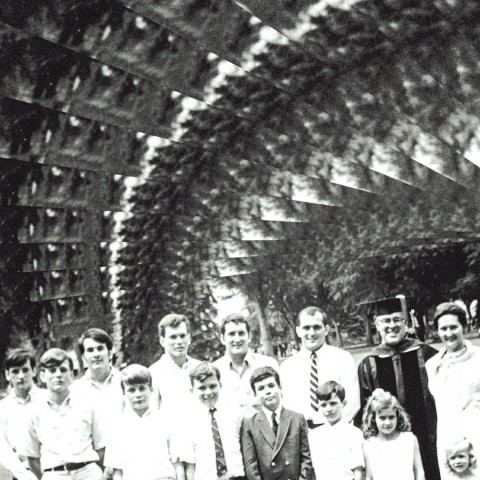

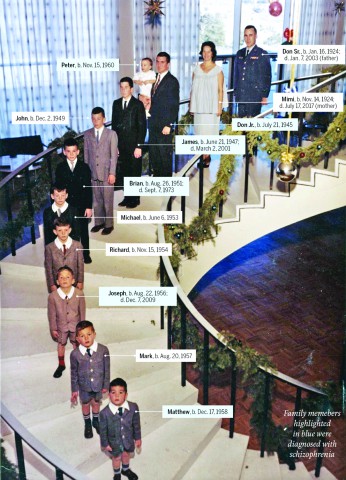

The story centres around the Galvin family who had twelve children over the period 1945 to 1965. By the time their all-American brood were young adults, six of the ten boys were diagnosed with schizophrenia and two of the girls had to face a cycle of abuse, neglect and occasionally removal from their home. The family was born at a time when there were a lot of advances in medical treatment – ranging from electric shock therapy to doses of Valium and Lithium, medication so strong that it caused side effects as dangerous as the disease itself.

Its author Robert Kolker writes in such a gripping, sensitive way that one roots for the family members to be well again, even though we know that will never happen. The care-givers suffer their own trauma. The ones who are ill refuse to recognize that they were unwell, and the ones who had to endure them suffer from burnout, resentment against their parents and varying attitudes from “I can fix things” to “I want to escape.”

The Galvin parents knew of the genetic condition after their first child grew violent and in turn abused younger siblings. They chose to ignore his psychotic behavior. They did not want to deal with it and wished it away. They felt they needed to preserve their relationships with the sick children, often at the cost of those who were well: vulnerable as they were as caregivers and also as potential victims to this disease.

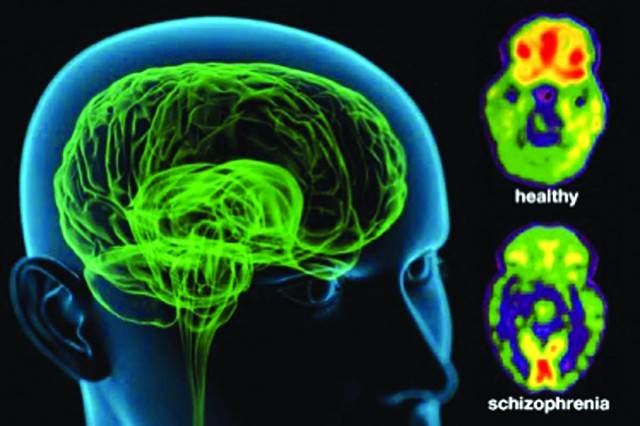

It did not help that during those days, medical disease was also the subject of the huge controversy of Nature vs Nurture. Though certain conditions can be genetic – as was the case with this family whose sons succumbed to the illness as teens – life course and trauma can play a key role. The Galvin case provide valuable case history and genetic samples to be studied by the newly formed National Institute of Mental Health.

Father Galvin was a decorated war hero. Mother Galvin could not help feeling a failure, even though she did her best to be a good mother to her children: “I baked a cake and pie every night or at least gave them Jello with whipped cream.”

The mother’s words sound very familiar: frozen by a sense of guilt and responsibility, too scared to get as much help as was needed to navigate a terrible situation. “It just freezes you because you don’t know what to do. You have nobody to speak to. We were an exemplary family . Everyone used us as a role model. And when it first happened, we were mortally ashamed”. And the feeling of shame, fear of others and what they will say or think and the loneliness on the path to recovery are common among families who battle this and other diseases.

We tell ourselves stories to survive. The Galvin one is interesting as to how each person in the family navigated care of the sick while also trying to process the impact on themselves, particularly seeing the elders fall victim to the disease. The sisters shared the mistake the family made: that to lose someone to the disease does not mean one loses the person, one still has to bridge the gap and reach out to the sick individual.

This was supported by medical research during the 1950s into the 1970s by Silvano Arieti, who wrote: “The cognitive process may be unconscious, or automatic or distorted, but it is always present.” Even at the worst of times, the brothers could notice kindness from others rather than being avoided as if they had a contagious disease.

What makes Kolker’s book compelling is the parallel narrative of the doctors who fought to research an underfunded disease. DeLisi, one of the doctors researching this illness and DNA, worked at Harvard Medical School and did not get the same awards or grants as other contemporaries. Pharma companies were not interested. It was a niche illness with a limited market, too small to spend money in new drug discovery.

This raises the issue of whether science should be available to the world as a public good rather than being controlled by large pharmaceuticals. This has become particularly relevant today as we debate why the COVID vaccine should not available to those who cannot afford it rather than being supplied first to those who can.

The Galvin family lived beyond the boundaries of suffering. They navigated the disease by being open to the research dimensions and working with doctors to make their experience the subject of research so that science could help future generations. No wonder that doctors always ask about family medical history and conditions as it is a vital part of our medical health mosaic. Ultimately, those before us are the key to understanding how genetics translate into hereditary illnesses. To know is to understand and to treat accordingly. In short, our family histories will be the histories of our future generations.

Even the Queen of England has not escaped. One episode in Season 4 of The Crown reveals the Queen Mother’s secret Bowes-Lyon cousins who were kept in a sanatorium for most of their lives, away from the public gaze. It is only when Princess Margaret sought professional help that the therapist disclosed the need to explore the family history. The cousins she had presumed dead are actually in a sanatorium to avoid the social stigma of the time.

Though The Crown takes creative liberties with the story, the Queen Mother’s reaction is all too familiar: “Their illness, idiocy and imbecility will make people question the integrity of the bloodlines. Can you imagine the headlines if that were to get out?”. This conversation could easily play out among many blue-bloods in any country.

Mental health issues are almost never spoken of publicly, particularly when marriages are being arranged. And in some cases, marriage is even considered a 'solution' to mental health issues. The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed that more than ever mental health issues can no longer be ignored. They need to be confronted directly, openly and compassionately.

Burying one’s secrets in the sand or deliberately ignoring such issues does not evaporate them. This is not the stuff of books. One has only to look about one to see that mental health issues abound. They need to be dealt with through patience, care, kindness and more often than not: professional help.

If you have not done so, please do read Read Hidden Valley Road by Robert Kolker, chosen by Oprah Winfrey for her book club pick in 2020. It is an actual account of a family of twelve children, born to Catholic parents in America during the 1950s. It is a riveting story - too wild yet true - of how mental illness can destroy families. The book is gripping: weaving a narrative using the genres of reporting and narrative non-fiction interleaved with the science of trauma and disease.

The mother’s words sound very familiar: frozen by a sense of guilt and responsibility, too scared to get as much help as was needed to navigate a terrible situation

The story centres around the Galvin family who had twelve children over the period 1945 to 1965. By the time their all-American brood were young adults, six of the ten boys were diagnosed with schizophrenia and two of the girls had to face a cycle of abuse, neglect and occasionally removal from their home. The family was born at a time when there were a lot of advances in medical treatment – ranging from electric shock therapy to doses of Valium and Lithium, medication so strong that it caused side effects as dangerous as the disease itself.

Its author Robert Kolker writes in such a gripping, sensitive way that one roots for the family members to be well again, even though we know that will never happen. The care-givers suffer their own trauma. The ones who are ill refuse to recognize that they were unwell, and the ones who had to endure them suffer from burnout, resentment against their parents and varying attitudes from “I can fix things” to “I want to escape.”

The Galvin parents knew of the genetic condition after their first child grew violent and in turn abused younger siblings. They chose to ignore his psychotic behavior. They did not want to deal with it and wished it away. They felt they needed to preserve their relationships with the sick children, often at the cost of those who were well: vulnerable as they were as caregivers and also as potential victims to this disease.

It did not help that during those days, medical disease was also the subject of the huge controversy of Nature vs Nurture. Though certain conditions can be genetic – as was the case with this family whose sons succumbed to the illness as teens – life course and trauma can play a key role. The Galvin case provide valuable case history and genetic samples to be studied by the newly formed National Institute of Mental Health.

Father Galvin was a decorated war hero. Mother Galvin could not help feeling a failure, even though she did her best to be a good mother to her children: “I baked a cake and pie every night or at least gave them Jello with whipped cream.”

The mother’s words sound very familiar: frozen by a sense of guilt and responsibility, too scared to get as much help as was needed to navigate a terrible situation. “It just freezes you because you don’t know what to do. You have nobody to speak to. We were an exemplary family . Everyone used us as a role model. And when it first happened, we were mortally ashamed”. And the feeling of shame, fear of others and what they will say or think and the loneliness on the path to recovery are common among families who battle this and other diseases.

We tell ourselves stories to survive. The Galvin one is interesting as to how each person in the family navigated care of the sick while also trying to process the impact on themselves, particularly seeing the elders fall victim to the disease. The sisters shared the mistake the family made: that to lose someone to the disease does not mean one loses the person, one still has to bridge the gap and reach out to the sick individual.

This was supported by medical research during the 1950s into the 1970s by Silvano Arieti, who wrote: “The cognitive process may be unconscious, or automatic or distorted, but it is always present.” Even at the worst of times, the brothers could notice kindness from others rather than being avoided as if they had a contagious disease.

What makes Kolker’s book compelling is the parallel narrative of the doctors who fought to research an underfunded disease. DeLisi, one of the doctors researching this illness and DNA, worked at Harvard Medical School and did not get the same awards or grants as other contemporaries. Pharma companies were not interested. It was a niche illness with a limited market, too small to spend money in new drug discovery.

This raises the issue of whether science should be available to the world as a public good rather than being controlled by large pharmaceuticals. This has become particularly relevant today as we debate why the COVID vaccine should not available to those who cannot afford it rather than being supplied first to those who can.

The Galvin family lived beyond the boundaries of suffering. They navigated the disease by being open to the research dimensions and working with doctors to make their experience the subject of research so that science could help future generations. No wonder that doctors always ask about family medical history and conditions as it is a vital part of our medical health mosaic. Ultimately, those before us are the key to understanding how genetics translate into hereditary illnesses. To know is to understand and to treat accordingly. In short, our family histories will be the histories of our future generations.