It is a story from my days of relative poverty. I was in college when I heard that a new edition of the famous Muraqqa-i-Chughtai was being published. It was in 1954, if I recall correctly

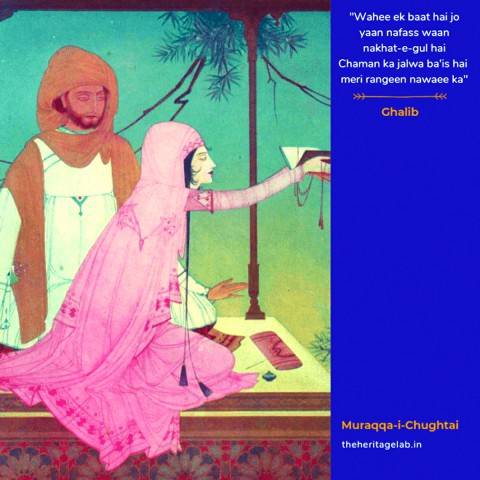

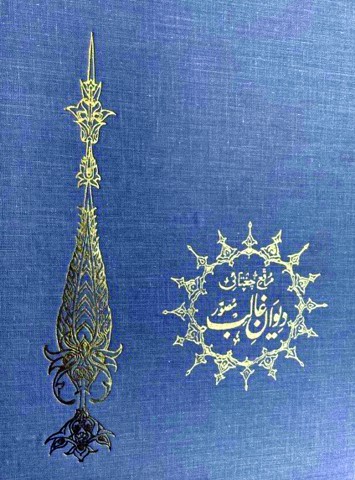

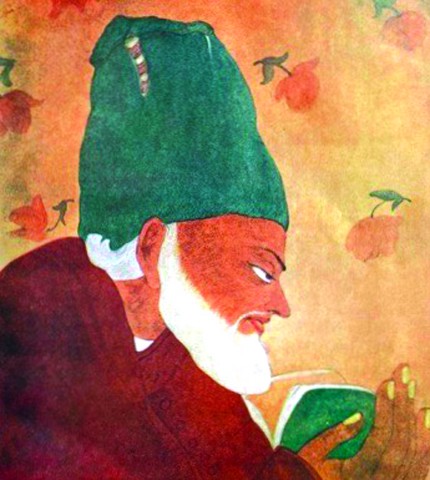

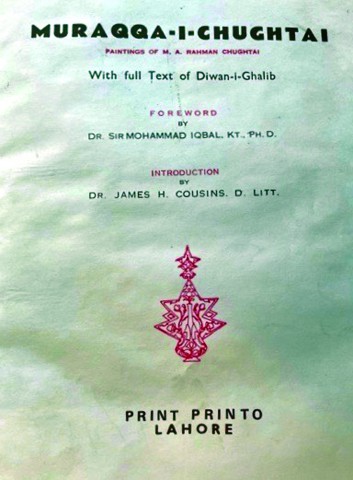

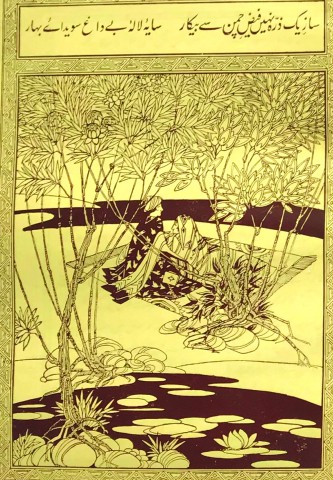

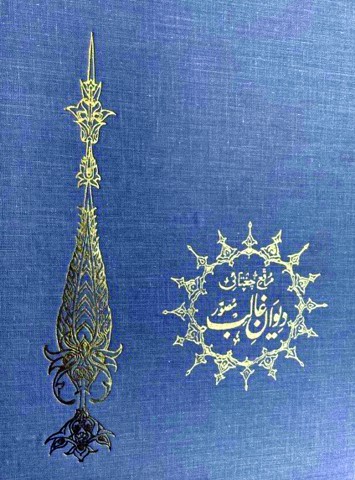

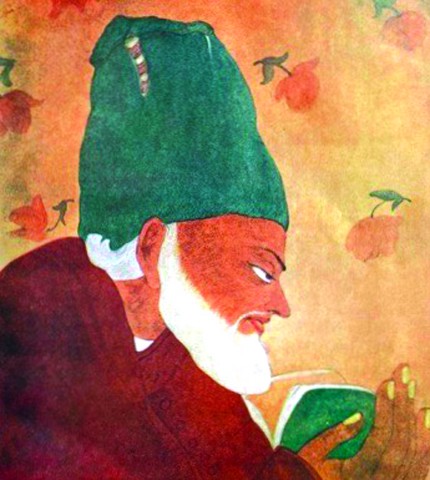

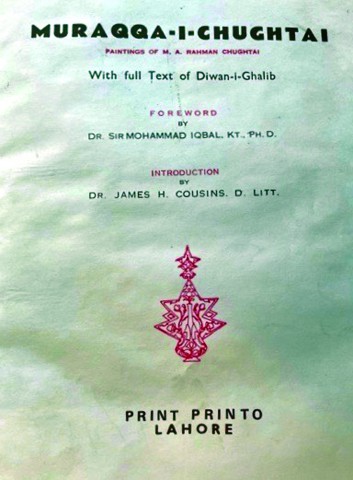

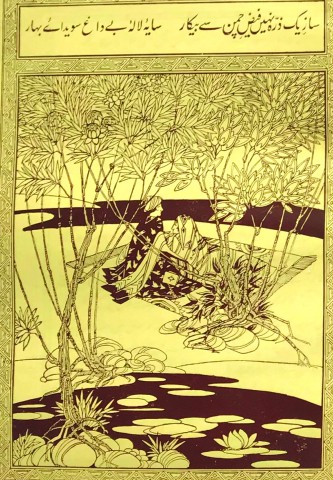

Originally published in 1928, the illustrated Diwan of Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib was considered an innovative effort to bring poetry and art together. The famous Pakistani poet Abdul Rahman Chughtai had rendered some of the couplets of Ghalib into paintings. Allama Iqbal (1877-1938) wrote the foreword and James Cousins (1873-1956) the Irish poet, playwright, critic and teacher wrote the introduction. In the ensuing decades the book found its way into oblivion – where many Urdu classics end up.

And now the edition was being resurrected for the benefit of lovers of poetry and art. There was, however, a big problem: as a college student I could not afford the price of few hundred rupees.

In fact, for a college student from a lower-middle-class family, there was always a juggling act between essentials and semi essentials. On occasions there was not enough money for essentials. As I have said in the past, there was always a lot of month left at the end of the money.

My childhood friend Siraj Ahmad and I share the love of literature and music. He promised to chip in whatever he could to realize my goal of buying the book.

My financial difficulty mirrored that of the English writer Charles Lamb (1775-1834). In a memorable essay titled “Old China,” the author and his cousin reminisce about their days when they were poor and could not afford to buy but the cheapest tickets to the theatre. They would stand in the pit in the center of the theatre to watch plays. And of how they would sneak in homemade sandwiches to a pub where they would buy only pint of beer and secretly eat their food with the purchased beer.

They had saved money to buy a bound volume of the plays of Beaumont and Fletcher. Once Lamb was convinced he wanted to spend the money on that volume, he could not wait for the morning. He went to the bookshop late in the evening and had the grumbling owner open the door and “lighted out the relic from his dusty treasures.”

With just enough money in my pocket, Siraj and I went to Ferozsons bookstore on Mall Road in Peshawar Cantonment. After taking possession of the book, I clutched it in my arms, and we made our way on foot to the city five miles away. We did not have extra coins to celebrate our purchase with a cup of tea at the Silver Star Café or to take a tonga ride to the city.

The book remained my prized possession for many years. I read and reread it and marveled at Chughtai’s paintings. Some were easy to understand but others defied simple explanations. In a way Chughtai’s art matched the complexities of Ghalib’s multi-layered poetry. It was brought home to me by Ahmad Faraz. On one of his occasional visits to my home in Toledo he picked up Diwan-e-Ghalib from my study for night reading. I joked that by this time he must remember each poem by heart. He said each time he reads Ghalib, he finds new meanings in his poetry.

I lost that book in the 1960s when I was travelling from Pakistan to the US. I reported the loss to Pakistan International Airlines (PIA). The agent asked me on the phone as to the price of the lost Diwan-e-Ghalib. I mentioned Rs.300. Upon hearing that the man became indignant and said that one can buy the book in Urdu Bazaar for a few rupees. It took me some time to explain the nature of the book to the man. He was clueless about Abdul Rahman Chughtai.

The next edition was published in the 1980s by Eewaan-e-Ishaat, Lahore. The edition carried the foreword and introduction that was in the original 1928 edition. It was priced at Rs. 400.

I saw the reproduced edition in a bookstore in Peshawar and I bought it on the spot. As I was leaving the bookstore, I could not resist remembering my experience with the earlier edition. I remembered a short poem by the late Ibn Insha:

I went to a festival with great expectations

I wanted to buy everything I saw

but what could I buy with an empty pocket

Those days of poverty and want are gone now

The festival is there again in its usual pomp and show

If I wish, I could buy all the shops

Even the world

The days of want and deprivation are long gone

But alas, I am not the same carefree young lad I once was

Here is Charles Lamb again:

“I wish the old times would come again, says his cousin, “when we were not quite so rich. I do not mean that I want to be poor; but there was a middle state in which I am sure we were a great deal happier. A purchase is but a purchase, now that you have money enough to spare.”

A number of years ago, I hosted a high tea for a few grand nieces and nephews at the Harrods, the famous store in London. The experience was enjoyable but not quite as much as having tea at Silver Star Café in Peshawar Cantonment. Siraj and I could barely afford a small teapot of tea. After we had squeezed the very last drop from the teapot, we would ask Nawaz the waiter if he would put some boiling water in the teapot. If he was in a good mood he would oblige, and we would have half cup each of slightly weak tea. If Nawaz was not in a charitable mood, he would take the empty teapot to the kitchen and bring us a full pot for which we had to pay.

So, I have my Muraqqa-i-Chughtai and in leisure I leaf through it and try to understand the paintings of Chughtai and also the verse of Ghalib. More than anything, this marvelous book connects me to my past.

Dr. Sayed Amjad Hussain is an emeritus professor of surgery and an emeritus professor of humanities at the University of Toledo, USA. His is also an op-ed columnist for the daily Toledo Blade and daily Aaj of Peshawar

Originally published in 1928, the illustrated Diwan of Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib was considered an innovative effort to bring poetry and art together. The famous Pakistani poet Abdul Rahman Chughtai had rendered some of the couplets of Ghalib into paintings. Allama Iqbal (1877-1938) wrote the foreword and James Cousins (1873-1956) the Irish poet, playwright, critic and teacher wrote the introduction. In the ensuing decades the book found its way into oblivion – where many Urdu classics end up.

And now the edition was being resurrected for the benefit of lovers of poetry and art. There was, however, a big problem: as a college student I could not afford the price of few hundred rupees.

In fact, for a college student from a lower-middle-class family, there was always a juggling act between essentials and semi essentials. On occasions there was not enough money for essentials. As I have said in the past, there was always a lot of month left at the end of the money.

My childhood friend Siraj Ahmad and I share the love of literature and music. He promised to chip in whatever he could to realize my goal of buying the book.

My financial difficulty mirrored that of the English writer Charles Lamb (1775-1834). In a memorable essay titled “Old China,” the author and his cousin reminisce about their days when they were poor and could not afford to buy but the cheapest tickets to the theatre. They would stand in the pit in the center of the theatre to watch plays. And of how they would sneak in homemade sandwiches to a pub where they would buy only pint of beer and secretly eat their food with the purchased beer.

They had saved money to buy a bound volume of the plays of Beaumont and Fletcher. Once Lamb was convinced he wanted to spend the money on that volume, he could not wait for the morning. He went to the bookshop late in the evening and had the grumbling owner open the door and “lighted out the relic from his dusty treasures.”

With just enough money in my pocket, Siraj and I went to Ferozsons bookstore on Mall Road in Peshawar Cantonment. After taking possession of the book, I clutched it in my arms, and we made our way on foot to the city five miles away. We did not have extra coins to celebrate our purchase with a cup of tea at the Silver Star Café or to take a tonga ride to the city.

The book remained my prized possession for many years. I read and reread it and marveled at Chughtai’s paintings. Some were easy to understand but others defied simple explanations. In a way Chughtai’s art matched the complexities of Ghalib’s multi-layered poetry. It was brought home to me by Ahmad Faraz. On one of his occasional visits to my home in Toledo he picked up Diwan-e-Ghalib from my study for night reading. I joked that by this time he must remember each poem by heart. He said each time he reads Ghalib, he finds new meanings in his poetry.

I lost that book in the 1960s when I was travelling from Pakistan to the US. I reported the loss to Pakistan International Airlines (PIA). The agent asked me on the phone as to the price of the lost Diwan-e-Ghalib. I mentioned Rs.300. Upon hearing that the man became indignant and said that one can buy the book in Urdu Bazaar for a few rupees. It took me some time to explain the nature of the book to the man. He was clueless about Abdul Rahman Chughtai.

My financial difficulty mirrored that of the English writer Charles Lamb (1775-1834). In a memorable essay titled “Old China,” the author and his cousin reminisce about their days when they were poor and could not afford to buy but the cheapest tickets to the theatre

The next edition was published in the 1980s by Eewaan-e-Ishaat, Lahore. The edition carried the foreword and introduction that was in the original 1928 edition. It was priced at Rs. 400.

I saw the reproduced edition in a bookstore in Peshawar and I bought it on the spot. As I was leaving the bookstore, I could not resist remembering my experience with the earlier edition. I remembered a short poem by the late Ibn Insha:

I went to a festival with great expectations

I wanted to buy everything I saw

but what could I buy with an empty pocket

Those days of poverty and want are gone now

The festival is there again in its usual pomp and show

If I wish, I could buy all the shops

Even the world

The days of want and deprivation are long gone

But alas, I am not the same carefree young lad I once was

Here is Charles Lamb again:

“I wish the old times would come again, says his cousin, “when we were not quite so rich. I do not mean that I want to be poor; but there was a middle state in which I am sure we were a great deal happier. A purchase is but a purchase, now that you have money enough to spare.”

A number of years ago, I hosted a high tea for a few grand nieces and nephews at the Harrods, the famous store in London. The experience was enjoyable but not quite as much as having tea at Silver Star Café in Peshawar Cantonment. Siraj and I could barely afford a small teapot of tea. After we had squeezed the very last drop from the teapot, we would ask Nawaz the waiter if he would put some boiling water in the teapot. If he was in a good mood he would oblige, and we would have half cup each of slightly weak tea. If Nawaz was not in a charitable mood, he would take the empty teapot to the kitchen and bring us a full pot for which we had to pay.

So, I have my Muraqqa-i-Chughtai and in leisure I leaf through it and try to understand the paintings of Chughtai and also the verse of Ghalib. More than anything, this marvelous book connects me to my past.

Dr. Sayed Amjad Hussain is an emeritus professor of surgery and an emeritus professor of humanities at the University of Toledo, USA. His is also an op-ed columnist for the daily Toledo Blade and daily Aaj of Peshawar