In 1947, British India witnessed a great division. It was all about the partition of land, heritage, material, and people – even insane patients were not spared. Newly formed governments of India and Pakistan resolved to transfer the insane patients based on religion. Therefore, Muslim patients in India were transported to Pakistan. Hindus and Sikhs were shifted from Pakistan to India.

Amritsar Mental Hospital’s report released on the 6th of December 1950 stated that the number of non-Muslim mental patients who came from Lahore, Peshawar and Hyderabad was 317 (223 male, 94 female), 55 (45 male, 10 female) and 78 (55 male, 23 female), respectively. In Amritsar, Indian officials again divided the patients based on language. So, 282 Punjabi-speaking patients were admitted to Amritsar Mental Hospital and the remaining 168 non-Punjabi speakers were transported to Mental Hospital Ranchi, Bihar, India (now in Jharkhand State, India.)

These were times of uncertainty. There were rumours of murders, rape and looting everywhere. The story was very simple, In Hindu areas, the story was about the rape and killing of Hindu or Sikh women by Muslims, and in Muslim pockets, the same story was told with reversed identities. These stories scaled the human migration manifold. Thus, a lot of qualified staff from Pakistan’s mental hospitals also migrated to India. The Mental Hospital Lahore also suffered when Lt Col. B. S. Nat opted for Medical Service of East Punjab, India. However, in the case of Sindh, Sir Cowasji Jahangir Mental Hospital was at less of a loss – because soon Dr. Ibrahim Khalil Sheikh and other staff members filled the void which mass migrations created.

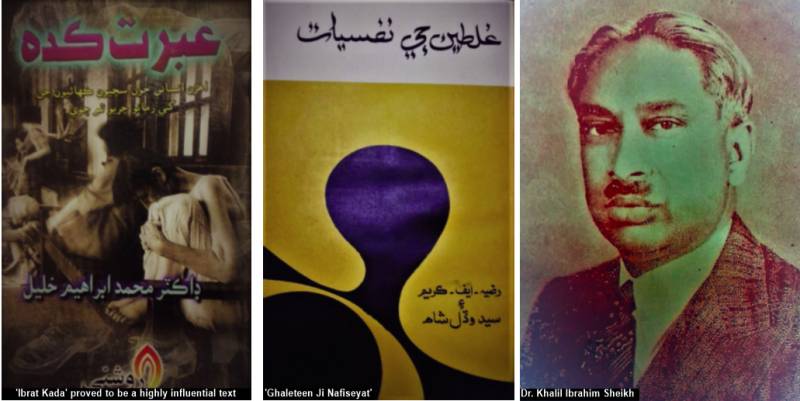

Dr. Ibrahim Khalil Sheikh was the one who, prior to Partition, introduced the case study method at Sir Cowasji Jahangir Mental Hospital, Hyderabad. These case studies later were fictionalized and published in three volumes with the title of Ibrat Kada. Dr. Sheikh wrote that one of the reasons for quickly writing and printing Ibrat Kada was the fear that after the Partition, Hindu mental patients were going to be shifted.

Books on psychology in the Sindhi language were available for ordinary readers since the 1930s. Most of these books were, however, either translated or adapted from Hindi, Urdu or Persian. Some popular names who authored or translated books on psychology were Hasanand Chandumal, Muhammad Bakhsh, Ghulam Raza, Veeromal Begraj, Ghulam Muhammad, Norang Zadah, and Kirshanand Gokaldas. One book entitled Ap Ghat - Utam Veechar (Suicide – Noble Thoughts) became popular and it caused some discussion for and against suicide, voluntary death and topics related to life and death.

Much later, the University of Sindh, Jamshoro, established the Sindh Science Society to promote science through various means including publication of books in Sindhi language. In the realization of its objective, the society published a booklet, Ghalteyn Ji Nafseyat (The Psychology of Errors) in 1975. It was the translation of Part 1 of Sigmund Freud’s book A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. Razia F. Karim and Syed Wadal Shah translated it into Sindhi. (The original book contained three parts; other two parts dealt with dreams, and common theory of the neuroses.) Later in 1990, another book Munjharan Mein Phathal Hik Shakhus (An Individual Trapped in Chaos) was also published. However, none of them in terms of quality and scholarship matched Ibrat Kada. In the 1980s, Ibrat Kada’s content, method, and systematic expression compelled a group of psychiatrists to translate some of the cases into English for the wider psychiatric community. Dr. Karim Khawaja and Professor Musarrat Hussain selected some case studies and translated it into English. The book was made available for limited circulation in 2005, with the new title Ibrat Kada – Revitalized. Mr. Anwar Pirzado, noted Sindhologist, authored its preface. Professor Musarrat Hussian’s insightful commentary made it relevant to the present times. He wrote that Dr. Ibrahim Khalil’s description of types and patterns of diseases through case studies was not so very different from the present times. Dr. Jamil Junejo, in conversation with this scribe, unpacked Professor Musarrat’s comment that present Sindh’s mental health profile listed depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychosomatic disorders, schizophrenia, seizure disorder – all of which were discussed in Ibrat Kada.

The word “Giddu” is used as a noun, verb, and adjective in Sindhi society. According to fiction writer and poet Dr. Waheed Jatoi, the “Giddu” word in Sindhi literature describes a state of mind – it communicates suffering, failure in love, betrayal, and rejection. However, its usage is contextual. It maybe a personal experience, satirical, moral and even a societal impression. Dr. Jatoi in this regard quoted two songs, one of which was popular in the 1970s:

Chario Aheyan, Charyan Khe Chhad,

Giddu Bandar Na Khule Dis

(I am insane, let the insane be alone

Don’t open Giddu’s doors to see me)

In the 1980s, another song, sung in duet by Rubina Haideri and Gul Hasan Mirani contained a reference to Giddu:

Thendeen Jann Chario Tu Hani

Wendeen Gidu Bandar Tu Sunbani

(Soon you will be mad,

Next day you will be in Giddu)

A pivotal point in Sindh’s psychiatric history was the passing of the Sindh Mental Health Ordinance in 2013. But the future of Giddu Mental Hospital, which is officially called Sir Cowasji Jahangir Pscharity (SCJIP), is still bleak.

Land grabbers have used various techniques to capture the land of the institution. In this regard a letter to the editor was published in one of the English dailies as to how in 2004 the then health secretary allotted a 4,125-square-yard plot from the institute’s land for the construction of the College of Physicians and Surgeons’ regional office, and in 2009 the Extended Programme on Immunisation was allowed to occupy the patients’ dining hall. The letter also stated that an NGO and the Sindh government signed the contract for building a 60-bed ward at the premises of the institute. Later, the said NGO handed over the project to another NGO and deserted.

Recently, the Sindh Governments’ health department has handed over the newly constructed first floor to the federal government’s narcotics control force through a Memorandum of Understanding. Like many politicians of Pakistan, Sindh’s legislators and political parties also attempted to grab the SCJIP’s land. Ardeshir Cowasjee quoted Dr Haider Ali Kazi (who was the one who nourished the institute from 1966, and protected its land till the last day of his retirement in 1999) that under the PPP government in 1973, Jam Sadiq Ali (the minister of housing and town planning in Sindh) and Abdul Waheed Katpar (the minister of health in Sindh) tried to grab the land with the apparent purpose of constructing a housing colony for low-income people.

Decades later, due to riots, Qasimabad emerged as a new town in the neighbourhood of Hyderabad city, and the area along with the Autobahn Road became an attractive business location for the traders and businessmen of Shahi Bazar, Saddar, Latifabad and Hirabad. Soon, shops of branded merchandise and offices of cell phone companies were opened at Autobahn Road. At that time, the MQM announced to establish a university in the area, but its hidden intention was to occupy the SCJIP’s land.

In Sindh, the SCJIP is popularly known as “Chariyan Ji Ispatal” or merely Giddu. However, one of its earlier names was “Sodaeen Jo Ashram”. Apart from the names, the location has given rise to satirical connotations and dark humour. Cynical voices made jokes revolving around the place and its inmates. There is a joke about Ayub Khan and an inmate. It runs thus: once Ayub Khan visited Giddu, where he introduced himself as the Field Marshal to a lunatic. The patient shook hands with him and replied that before landing at this place, he was also a Field Marshal.

Amritsar Mental Hospital’s report released on the 6th of December 1950 stated that the number of non-Muslim mental patients who came from Lahore, Peshawar and Hyderabad was 317 (223 male, 94 female), 55 (45 male, 10 female) and 78 (55 male, 23 female), respectively. In Amritsar, Indian officials again divided the patients based on language. So, 282 Punjabi-speaking patients were admitted to Amritsar Mental Hospital and the remaining 168 non-Punjabi speakers were transported to Mental Hospital Ranchi, Bihar, India (now in Jharkhand State, India.)

These were times of uncertainty. There were rumours of murders, rape and looting everywhere. The story was very simple, In Hindu areas, the story was about the rape and killing of Hindu or Sikh women by Muslims, and in Muslim pockets, the same story was told with reversed identities. These stories scaled the human migration manifold. Thus, a lot of qualified staff from Pakistan’s mental hospitals also migrated to India. The Mental Hospital Lahore also suffered when Lt Col. B. S. Nat opted for Medical Service of East Punjab, India. However, in the case of Sindh, Sir Cowasji Jahangir Mental Hospital was at less of a loss – because soon Dr. Ibrahim Khalil Sheikh and other staff members filled the void which mass migrations created.

Dr. Ibrahim Khalil Sheikh was the one who, prior to Partition, introduced the case study method at Sir Cowasji Jahangir Mental Hospital, Hyderabad. These case studies later were fictionalized and published in three volumes with the title of Ibrat Kada. Dr. Sheikh wrote that one of the reasons for quickly writing and printing Ibrat Kada was the fear that after the Partition, Hindu mental patients were going to be shifted.

Books on psychology in the Sindhi language were available for ordinary readers since the 1930s. Most of these books were, however, either translated or adapted from Hindi, Urdu or Persian. Some popular names who authored or translated books on psychology were Hasanand Chandumal, Muhammad Bakhsh, Ghulam Raza, Veeromal Begraj, Ghulam Muhammad, Norang Zadah, and Kirshanand Gokaldas. One book entitled Ap Ghat - Utam Veechar (Suicide – Noble Thoughts) became popular and it caused some discussion for and against suicide, voluntary death and topics related to life and death.

Much later, the University of Sindh, Jamshoro, established the Sindh Science Society to promote science through various means including publication of books in Sindhi language. In the realization of its objective, the society published a booklet, Ghalteyn Ji Nafseyat (The Psychology of Errors) in 1975. It was the translation of Part 1 of Sigmund Freud’s book A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. Razia F. Karim and Syed Wadal Shah translated it into Sindhi. (The original book contained three parts; other two parts dealt with dreams, and common theory of the neuroses.) Later in 1990, another book Munjharan Mein Phathal Hik Shakhus (An Individual Trapped in Chaos) was also published. However, none of them in terms of quality and scholarship matched Ibrat Kada. In the 1980s, Ibrat Kada’s content, method, and systematic expression compelled a group of psychiatrists to translate some of the cases into English for the wider psychiatric community. Dr. Karim Khawaja and Professor Musarrat Hussain selected some case studies and translated it into English. The book was made available for limited circulation in 2005, with the new title Ibrat Kada – Revitalized. Mr. Anwar Pirzado, noted Sindhologist, authored its preface. Professor Musarrat Hussian’s insightful commentary made it relevant to the present times. He wrote that Dr. Ibrahim Khalil’s description of types and patterns of diseases through case studies was not so very different from the present times. Dr. Jamil Junejo, in conversation with this scribe, unpacked Professor Musarrat’s comment that present Sindh’s mental health profile listed depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychosomatic disorders, schizophrenia, seizure disorder – all of which were discussed in Ibrat Kada.

The word “Giddu” is used as a noun, verb, and adjective in Sindhi society. According to fiction writer and poet Dr. Waheed Jatoi, the “Giddu” word in Sindhi literature describes a state of mind – it communicates suffering, failure in love, betrayal, and rejection. However, its usage is contextual. It maybe a personal experience, satirical, moral and even a societal impression. Dr. Jatoi in this regard quoted two songs, one of which was popular in the 1970s:

Chario Aheyan, Charyan Khe Chhad,

Giddu Bandar Na Khule Dis

(I am insane, let the insane be alone

Don’t open Giddu’s doors to see me)

In the 1980s, another song, sung in duet by Rubina Haideri and Gul Hasan Mirani contained a reference to Giddu:

Thendeen Jann Chario Tu Hani

Wendeen Gidu Bandar Tu Sunbani

(Soon you will be mad,

Next day you will be in Giddu)

A pivotal point in Sindh’s psychiatric history was the passing of the Sindh Mental Health Ordinance in 2013. But the future of Giddu Mental Hospital, which is officially called Sir Cowasji Jahangir Pscharity (SCJIP), is still bleak.

Land grabbers have used various techniques to capture the land of the institution. In this regard a letter to the editor was published in one of the English dailies as to how in 2004 the then health secretary allotted a 4,125-square-yard plot from the institute’s land for the construction of the College of Physicians and Surgeons’ regional office, and in 2009 the Extended Programme on Immunisation was allowed to occupy the patients’ dining hall. The letter also stated that an NGO and the Sindh government signed the contract for building a 60-bed ward at the premises of the institute. Later, the said NGO handed over the project to another NGO and deserted.

Recently, the Sindh Governments’ health department has handed over the newly constructed first floor to the federal government’s narcotics control force through a Memorandum of Understanding. Like many politicians of Pakistan, Sindh’s legislators and political parties also attempted to grab the SCJIP’s land. Ardeshir Cowasjee quoted Dr Haider Ali Kazi (who was the one who nourished the institute from 1966, and protected its land till the last day of his retirement in 1999) that under the PPP government in 1973, Jam Sadiq Ali (the minister of housing and town planning in Sindh) and Abdul Waheed Katpar (the minister of health in Sindh) tried to grab the land with the apparent purpose of constructing a housing colony for low-income people.

Decades later, due to riots, Qasimabad emerged as a new town in the neighbourhood of Hyderabad city, and the area along with the Autobahn Road became an attractive business location for the traders and businessmen of Shahi Bazar, Saddar, Latifabad and Hirabad. Soon, shops of branded merchandise and offices of cell phone companies were opened at Autobahn Road. At that time, the MQM announced to establish a university in the area, but its hidden intention was to occupy the SCJIP’s land.

In Sindh, the SCJIP is popularly known as “Chariyan Ji Ispatal” or merely Giddu. However, one of its earlier names was “Sodaeen Jo Ashram”. Apart from the names, the location has given rise to satirical connotations and dark humour. Cynical voices made jokes revolving around the place and its inmates. There is a joke about Ayub Khan and an inmate. It runs thus: once Ayub Khan visited Giddu, where he introduced himself as the Field Marshal to a lunatic. The patient shook hands with him and replied that before landing at this place, he was also a Field Marshal.