Lingering echoes of a violent past

According to a 2022 study by the Centre for Research & Security Studies, between 1947 and 2021, 89 people were killed in Pakistan for allegedly committing blasphemy. There were roughly 1,500 accusations and cases during this period. More than 70% of these were in Punjab.

Incidents of blasphemy accusations and killings in other provinces of Pakistan are much lower. Sindh comes a distant second with 173 accusations and nine killings, followed by Islamabad with 55 accusations and two killings. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) has recorded 33 accusations and six killings. Balochistan, Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan have the lowest numbers. There have been no killings in the latter two regions and just one in Balochistan.

From 1948 till 1985, just 11 cases of blasphemy were recorded in the country and three killings. This was when the blasphemy laws of the country did not carry the death sentence. From the period when the death sentence was introduced in 1986, the number of cases went up by 1,300%.

But why has Punjab been the hotbed of blasphemy-related cases, violence and deaths? Even during the period when the blasphemy laws were much lighter, there were two killings here. Both the victims belonged to the Ahmadiyya community. Punjab has become the epicentre of blasphemy-related violence. Political scientists Dr Muhammad Waseem and Christophe Jaffrelot have pondered whether this is in any way linked to the lingering impact of the vicious ‘communal violence’ which erupted in Punjab during the partition of India in 1947.

The region was the scene of widespread riots and clashes between Muslims on the one side and Hindus and Sikhs on the other. Thousands were killed. Many prominent radical Hindu nationalist and Islamist organisations were headquartered in Punjab. Apart from being involved in violence against each other, these outfits were also brawling with mainstream political parties such as Jawaharlal Nehru’s Indian National Congress and Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s All India Muslim League (AIML).

This type of violence is comparatively low in other provinces, but Punjab has become the epicentre of blasphemy-related violence. Political scientists have pondered whether this is in any way linked to the lingering impact of the vicious violence which erupted in Punjab during the 1947 partition

The Hindu nationalists wanted a ‘Hindu Rashtra’ (Hindu State) which they believed the ‘secular’ Congress was unwilling to create. The radical Islamists, on the other hand, attacked the AIML for being a ‘secular’ party, incapable of creating an Islamic State. Islamist organisations in the Punjab, such as the Majlis-i-Ahrar, also accused the League of having ‘deviant Muslims’ (ie Shia and the Ahmadiyya) in its ranks.

To address the accusations aimed at it by the Islamists in Punjab, the League was compelled to alter its message. In other Muslim-majority regions of India, such as East Bengal and Sindh, and in regions where the Muslims were in a minority, the League posited a Muslim nationalism that was territorial. The party highlighted this nationalism’s economic and political benefits. But in Punjab, despite the fact that 51% of the population was Muslim, the League’s message was failing to gain much traction.

So, during the 1946 provincial elections in British India, the League had to engage certain powerful land-owning pirs (spiritual guides) and ulema in Punjab. To rouse the Muslims of the province, especially in the rural areas, the pirs and the ulema were allowed by the party to drift away from the League’s nationalist manifesto and add a radical dimension to its message.

They began to frame the ‘Westernised’ constitutionalist Jinnah as an ideologue who was striving to create a ‘new Madinah’ and/or an Islamic state that would be navigated by pious men and Shariah laws. Nothing of the sort happened, of course, after Jinnah succeeded in creating Pakistan. But a large portion of Punjab’s Muslim population was thoroughly radicalised.

Partition triggered unprecedented violence in Punjab. When the western part of the province became part of Pakistan, the Muslims here became an overwhelming majority. The number of Hindus and Sikhs dwindled. With these gone, the residue of communal violence, and the fires lit by lofty Islamist rhetoric of 1946, rebounded towards the Ahmadiyya. There is, thus, nothing surprising about the fact that the two violent anti-Ahmadiyya movements (1953 and 1974) were both centred in Punjab.

The 1974 anti-Ahmadiyya movement whose epicentre was Punjab, compelled the Parliament to constitutionally oust the Ahmadiyya from the fold of Islam. The besieged mindset that emerged in Punjab during 1947 violence then diverted its lingering energies towards alleged blasphemers — especially after 1986.

Punjab also has one of the largest populations of Barelvi Sunni Muslims in the country. This Sunni sub-sect felt alienated and threatened when the ‘Islamisation’ policies of the Gen Ziaul Haq dictatorship were perceived to have benefitted the rival Deobandi Sunni sub-sect.

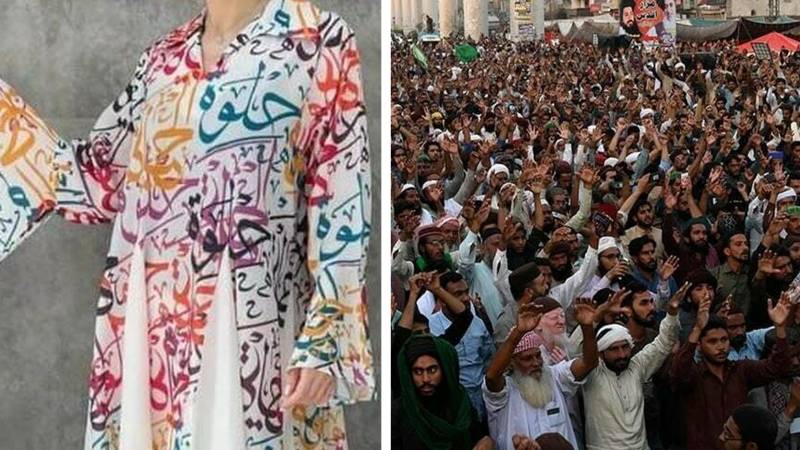

As a response, radical Barelvi leaders began to adopt the ‘defence’ of the blasphemy laws as their main calling. There was especially a tenfold spike in incidents of blasphemy-related violence and deaths in Punjab after 2011 — the year when a member of a Barelvi evangelical outfit assassinated the Governor of Punjab, Salman Taseer. The killer had accused him of criticising the blasphemy laws.

The British in India introduced four blasphemy laws, apparently to control the radical polemics between Hindus and Muslims. The laws did not include the death penalty, though. In 1927, a sterner law was imposed after a Muslim murdered a Hindu for writing an offensive book against Islam

One of the reasons behind the spike was also that the assassin was hailed as a ‘hero’ by many. He was then unabashedly praised by some prominent politicians of Punjab. Taseer was murdered in January 2011. 110 more cases and accusations of blasphemy were recorded during the same year in Punjab. These increased to 263 in 2014. 2020 witnessed another spike with 231 cases.

So what’s the way out? Some concerned commentators have suggested that since no state institution or government is willing to undo the controversial 1986 addition to the blasphemy laws, one can at least ‘balance’ the law by adding equally damning punishments for those concocting false accusations of blasphemy.

But Islamist parties refuse to even discuss this. These laws have continued to normalise blasphemy-related violence. Rampaging mobs actually believe they are doing something that is not only divinely ordained, but also entirely lawful.

This nature of violence is comparatively low in other provinces. So one can conclude that this is largely because Sindh, KP and Balochistan did not witness the brutal degree of violence in 1947 as did Punjab and whose impact and rhetoric has continued to impact the polity in the province. Punjab was also the hub of vicious sectarian and religious polemics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Blasphemy laws in Pakistan: a brief history

Till the 1930s, there was no real concept of a law against blasphemy in the Muslim world. Therefore, nor was there such a law in an India that was ruled by Muslim dynasties for over six centuries. It was the British colonialists who, in 1860, first introduced laws against blasphemy in South Asia. European regions had had a history of enacting such laws. It was in 14th-century France that the concept of a blasphemy law was first shaped and imposed. There was a blasphemy law in Britain as well when the country completely conquered India in the 19th century.

In 1880, the British in India introduced four blasphemy laws, apparently to control the radical polemics between Hindus and Muslims. The laws did not include the death penalty, though. In 1927, a sterner law was imposed after a Muslim murdered a Hindu for writing an offensive book against Islam. This law was then adopted by Bharat and Pakistan after the British departed from India.

The punishment for blasphemy according to this law included one-year imprisonment or a fine or both. It was from 1980 onwards that these laws began to be expanded and the intensity of the purposed punishment increased, culminating with the addition of the death penalty in 1986.

Blasphemy laws in the Muslim world

From the 7th century till the early 20th century, there is not a single recorded incident where any blasphemy laws were enacted in a Muslim-majority region. Indeed, over the centuries many Islamic theologians debated the concept of blasphemy in Islam. While the Muslim holy book, the Quran, looks down upon blasphemy, it does not prescribe any punishment for it. It is due to this that blasphemy laws were never enacted in a Muslim-majority region till the early 20th century.

The first blasphemy law to appear in a Muslim-majority country was in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia had come into existence in 1932 with the help of the British. It adopted an ultra-conservative strand of Islam. Saudi laws prescribed death by beheading for blasphemy.

Libya enacted a blasphemy law in 1953. It prescribed fines and some years of imprisonment.

Indonesia was the third major Muslim-majority country to enact blasphemy laws. It did so in 1965. The punishment prescribed was a 5-year jail sentence and fines. In 2008, a powerful Islamic lobby made a bid to successfully restrict the activity of the Ahmadiyya in Indonesia. However, the move was not made part of the law and was adopted by just a handful of Indonesia’s provinces.

Afghanistan enacted a law called “Crimes Against Religions” in 1976. But this lapsed during the Soviet-backed government in Kabul between 1978 and 1988. In 1996, the first Taliban regime unleashed a reign of terror, enforcing various laws that prescribed the most brutal death sentences. These lapsed after the fall of the Taliban in 2001.

However, with a US-backed ‘democratic’ government at the helm, the “Crimes Against Religions” returned in 2004, and this time it prescribed the death sentence for blasphemy. But if a convicted person took back his ‘blasphemous views’ and repented within two days, he or she could be forgiven. One is not sure what the status of this law in Afghanistan is today, with the Taliban back in power.

Pakistan and India adopted the blasphemy laws which the British introduced. They were mild and hardly ever used by both the countries. The punishment prescribed by this law was one-year imprisonment or a fine. India has continued to retain this law.

In 1980, after the 1977 reactionary military coup in Pakistan, two more years were added to the punishment for committing blasphemy. In 1984 a punishment of 3 years imprisonment was added to the law for the Ahmadiyya guilty of preaching Islam or for calling themselves Muslims. They had been constitutionally ousted from the fold of Islam by Pakistan in 1974.

In 1986, the death sentence was added to the blasphemy law through an ordinance. This ordinance lapsed in 1991, but was re-enacted by an elected parliament. Ever since 1991, Pakistan has had the most number of people languishing in jails, facing blasphemy charges. There have also been a large number of incidents in which enraged mobs or individual vigilantes have killed those accused of committing blasphemy. The law does not carry any punishment for false allegations.

Blasphemy laws in Iran were first introduced right after the 1979 Islamic Revolution there. They prescribed death by hanging or a firing squad. Iran still has these laws which are often used against political dissidents.

Egypt enacted a blasphemy law in 1981. Though it does not carry the death sentence, it has often encouraged vigilante violence. UAE, Qatar, Algeria, Oman, Jordan, Malaysia, Somalia, Sudan, Morocco and Yemen are some other Muslim nations which have blasphemy laws. Among these, only blasphemy laws in Yemen and Somalia carry the death sentence. Out of the former communist countries with Muslim majorities in Central Asia and Europe, only one, Kazakhstan, has a blasphemy law.

Muslim-majority regions that have blasphemy laws which carry the death sentence are Iran, Pakistan, Libya, Afghanistan, Somalia and Yemen. Such laws in the Western world have lapsed or have been repealed.