As expected, the dust of Aitchison has settled very quickly with the departure of Michael Thompson, its Australian principal, but not without a reminder once again that the institution is a perfect representation of the sense of entitlement of the country’s ruling elite. This is hardly surprising, since it was meant to be their preserve, and has remained so for the past 140 years. Going back to its foundational principles, the institution was conceived as a “Punjab Chiefs’ School” and it was meant to be “a sort of Punjab Eton, to which boys of good family should be admitted and where the education should be thorough and the fees high” (Punjab Administration Report, 1884-1885). Much careful thought had gone into this. The ‘Education of Indian Chiefs’ was a policy priority that had occupied the minds of the British Government in India. Sir John Lawrence (Chief Commissioner of Punjab, later its provincial lieutenant-governor,1849-1859, as also the Viceroy of India, 1864-1869) had ensured British victory over the mutineers of 1857 because the Chiefs of Punjab had risen almost unanimously to his call to suppress the Indian Mutiny.

The historical context is both interesting and relevant. In 1852, at the time of the renewal of the Charter of the East India Company, the Lords’ Committee of the British Parliament (not the British Indian Administration in Calcutta) had decided on a comprehensive scheme of education for an Indian elite based on “diffusion of the improved arts, science, philosophy and literature of Europe; in short of European knowledge.” An adjunct to this policy was the special and preferential treatment to be accorded to the boys of the Punjab Chiefs, whose curriculum and outlook were meant to be somewhat different from those of the Missionary English and American schools. Towards this end, special classes were held at the Lahore Government School in 1859-1860 for sons of Punjab Chiefs. These came to be known later (1871-1873) as the “Sardars’ Class”-- akin to the Wards’ School at Ambala which catered to the same privileged class with a curriculum coupling English and Vernacular instruction with horse riding and physical education, being the hallmarks of a gentleman of the ruling class. The Sardars Class was limited at the time to only 12 scions of the Punjab Chiefs. But they were a crucial instrument of that imperial policy of ensuring feudal loyalties that had so successfully been initiated by Sir John Lawrence in 1849.

The full credit for instilling the educational ethos of privilege and quality must, however, go to John Lawrence’s ardent disciple, the scholarly Charles Umpherston Aitchison, the lieutenant governor of Punjab (1882-1887), who founded both the Punjab University (1882), fashioned after London University, and the Punjab Eton which has been named after him ever since 1886. The driving force behind the founding of Aitchison College, as reported in the Punjab Administrative Report (1884-1885), cited above, was Lord Aitchison’s Indian Education Report (1882-1883) that carried three different strands and proposed separate measures for the education of Indian Chiefs, of Mohammadans and of oppressed classes. The sense of entitlement and exclusivity that Aitchisonians have carried ever since springs from this privileged consideration.

The old grandees and the bourgeois upper middle class - which replaced the aristocracy of yesteryear - both want the privilege of admission for their offspring. This is simply not possible, because there are never enough spaces

Privilege and entitlement, the distinctive features of this institution, as indeed that of the national polity of which it is a microcosm (please see The Friday Times of 31 March 2024 on this subject), however, carry with it their own equally manifest nemesis– which must eventually catch up with it.

Aitchison can be and has been used as a case study of the efficacy of privileged social elites maintaining their hold on power in Pakistan. Anthropologist Rosita Armytage in her 2020 book, Big Capital in an Unequal World: The Micropolitics of Wealth in Pakistan, showcases Aitchison as a perfect example of ‘elite male networking’ on the part of the old feudal elite, the industrial business class, the upper echelons of the civil-military bureaucracy – both in competition and in collusion with one another – to retain exclusive control over the prestigious educational institutions and social clubs in Lahore. Nothing exemplifies the working of this elite consensus better than the two places in the heart of Lahore –Aitchison and the Punjab Club – known for something like a century as the ultimate elite preserve of status. An “elite” is often an amorphous and multi-faceted social composition; it can be elusive and intractable (analytically) – yet an institutional case study, such as the one done by Rosita Armytage on Aitchison will irradiate its working. Armytage highlights the contest between the nouveau riche (and thus inferior) trading class and the old wealth to access Admissions to the school for their male offspring. The struggle, as noted by her, is between the parvenu class seeking “merit” as a criterion for admission, as against the “historical nepotism” (Armitage’s words) that the Old Boys have historically become accustomed to. She gives the telling example of a first-time enforced move (in 2015) by the then-Principal for an exclusively merit-based admissions policy, which so threatened the ingrained nepotism of the old elite guard that the Principal had to be sacked and that policy swiftly reversed. The Guardian also reported this at that time.

The old grandees and the bourgeois upper middle class (especially the nouveau riche traders of Lahore), which has replaced the aristocracy of yesteryear, both want access to the privilege of admission to this school for their offspring. This is simply not possible, because there are never enough spaces available. What compounds the problem is a further desire, especially on the part of the Old Guard, to preserve and maintain the exclusivity of that privilege. In other words, to keep the institution a closed shop, because such exclusivity is what burnishes its brand name. This has always been its hallmark since its inception. It succeeded in doing so for the first 70-odd years of its existence. Its vast physical and financial resources catered, for instance, to only 250 boys (as far as I can personally remember when I joined in 1952). A decade later (1962, when I left the school) the average intake (I believe) was 360 or something akin to that. The sheer demographic pressure in subsequent years has led to (perhaps) a ten-fold growth. The inevitable consequence of this is the transformation of the nation’s Chiefs’ College to a bourgeois School of the City of Lahore alone, albeit one with an elitist image still. In this process, the post-partition demographic explosion, the increased populism and the Dubai boom starting in the early 1970s have resulted in all but the disappearance of the basic club-like features of the school, especially the esprit de corps among its students. For instance, students of any one class, which now has 8-10 Sections, hardly know more than a dozen classmates. 60 years back hardly any class had more than one Section and class size was seldom, if ever, more than 25. Every student knew every other student very well and in most cases, they kept up with one another in subsequent years.

In two other fundamental respects, the institution is not recognisable from what it was five decades back. In the 1990s, it lost what was its basic pride: its excellence on the sports field. Sports were no longer made compulsory (as they used to be until then), although some feeble attempts have been made recently for a sort of revival. An even more fundamental change in institutional character is its representative character. It used to be an all-Pakistan school, with boys coming from all four provinces of the country and even from East Pakistan. The natural corollary to this was that it was once, as it was always meant to be, primarily a boarding school with a national outlook. Now, about 90% of its intake is from urban Lahore. As a consequence, the Boarding Houses, the school’s pulsating organs, much like the Oxbridge Colleges within the University, have atrophied almost to extinction.

Nonetheless, despite this sea change, and bereft of all its original exclusivity, its sheen, distinction, purpose and fundamental characteristics, it remains the school of choice, albeit a local Lahore city school, not a national all-Pakistan school. How and why has it retained its brand name and appeal?

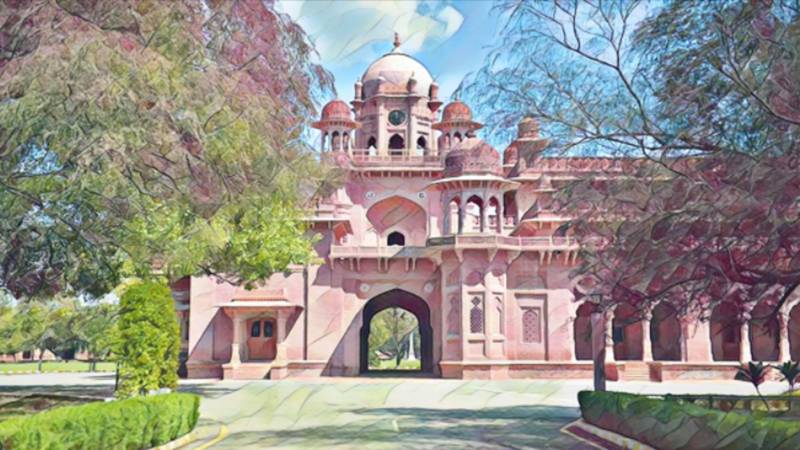

Aitchison’s main attraction is what it has always been– its splendid playfields, lawns and gardens tended by 400 gardeners, its richly endowed physical infrastructure, including its historic Old Building which is seldom used but remains an iconic relic displayed on every school poster. The aura of grandeur and privilege that the place exudes has always been, and remains, its defining feature. Aitchison has never been a place of much learning or academic excellence. Nor was it meant to be. For academic achievement, one sent the boy to St Antony’s and perhaps now to one of the Grammar Schools. Aitchison served an entirely different purpose — and that purpose remains the same: to cater to the maintenance of a small establishment of vested interests at disproportionately colossal public expense. In this regard, Aitchison has never changed. I cannot think of a better way to say it than in the words of one of its former Presidents of the Board (Council), the Governor of Punjab, 88 years back. Reproduced below is an excerpt from a fortnightly report of Governor Emerson to Viceroy Lord Linlithgow. It is dated 16 November 1936.

“The Aitchison College has at last decided to make some move with the times. It provides for the sons and relatives of Ruling Princes of the Punjab States, and of leading families in the Punjab. The rules of admission have remained practically unchanged since the college was founded more than 50 years back. They are very exclusive, and, as a result, the college has been unable to compete either in numbers or in education with less aristocratic institutions. It has very fine buildings and excellent grounds, and could easily be made one of the best educational colleges in India. It has at present a keen and progressive Principal (Mr Barry), who has already done much for it. We have been trying for the last three years to get the Committee of Management and the Council to liberalise the rules of admission, but, owing largely to His Highness the Maharaja of Patiala, it was not possible to force the pace too rapidly. I am glad to say, however, that the Council has now universally adopted much more liberal rules. Patiala behaved very reasonably and, although the new rules are still restrictive, they are far more liberal than the old ones. I am hoping that the number of boys, which is just over 100, will very considerably increase, and that we shall be able to improve the staff and the educational standards. The question is of considerable importance, since it is largely to the Aitchison College that one must look for men of good families in the Punjab to take a worthy part in the services and public affairs. Undoubtedly a strong influence in favour of change has been an appreciation of the fact that the new Constitution threatens vested interests, and that merit will be a more searching test in the future than in the past. That is all to the good.”

Emerson’s fond hope of merit was never realised. The ‘rules of admission’ remain restrictive, and “as a result, the college has been unable (in its entire history) to compete either in numbers or in education with less aristocratic schools.” It could never “be made one of the best educational colleges” (academically) in the country. The pride of its “very fine buildings and excellent grounds” is no more than a showcase for the self-serving egos of the threatened “vested interests” that Emerson pointed towards with such clarity and prescience.

All this underlines my ultimate quest to find a justification for the vast outlay of state resources to cater to the narrow benefit of those “vested interests”. This leads inevitably to my final question: can it not be said that Aitchison has lost its raison d’etre?